ABQwerty Type Writer Society Meeting, Mega-Big Cameras, B/W Peroxide Reversal Process

One of two machine I brought to the ABQwerty Type Writer Society meeting.

Notice how I underlined my mispelled words, drawing even more attention to them! And then this comment adds even more attention yet!

The other machine I brought to the gathering, an early 1960s Hermes 3000.

This is the kind of surprise inspiration that I find common with using typewriters, especially a machine like the Hermes 3000 (but not exclusive to it), that disappears into the background, providing a true undistracted writing experience that serves to unlock the hidden thoughts from within.

In the month since I've last blogged, I've also been busy in my spare time helping Ethan Moses with building and using the mega-sized 20" x 24" view camera and associated self-developing back. It's actually three projects in one: a mega-sized 20" x 24" view camera (with a sub-project of crafting a functional mega-sized bellows using a novel internal stiffener material); a self-developing back (a combination film holder and processing tank in one) made from laser-cut sheet acrylic; and further refinements to the B/W citric acid / hydrogen peroxide reversal process.

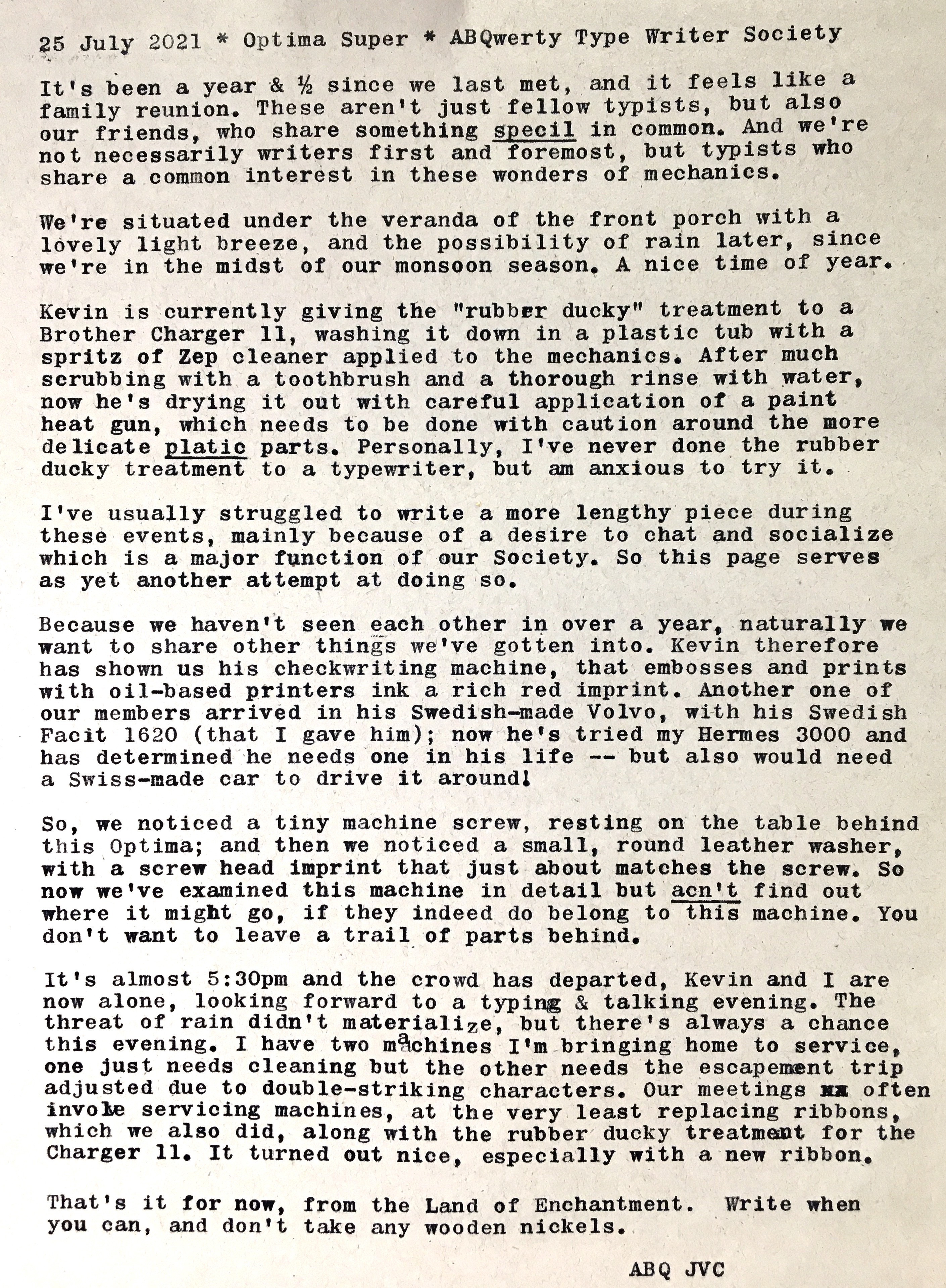

Ethan with an earlier version of the 20" x 24" camera.

I've documented much of this project in these two videos, that I call The Dream.

The Dream Part One:

The Dream Part Two:

The black and white reversal process was something I heard of a few years ago on APUG (now known as Photrio) and I soon began experimenting with it. Reversal processing is a way to get a positive image from a black and white print paper where normally you'd get a negative image.

For example, if you load a sheet of B/W paper in a camera and expose it like film, then develop in standard chemistry, you end up with what's known as a paper negative. This is because the light-sensitive silver salts in the paper emulsion turn black when processed in standard developer chemistry, if they've been exposed to light. The parts of the paper that haven't been exposed to light remain paper-white; hence the image ends up as a negative (bright parts of the scene are dark on the paper and dark parts of the scene are light on the paper). This is a handy thing if you're using such paper for its intended purpose of making prints from photographic negatives. Because the print's tones are a negative of the negative's tones, the image on the print ends up as a positive.

But what if you want a direct positive print straight out of the camera, using print paper as your film? The traditional way of doing this so-called "reversal" processing uses potasium dichromate and sulfuric acid, both dangerous chemicals to handle and dispose of safely. But this new way I discovered of doing reversal processing uses citric acid and concentrated hydrogen peroxide, along with standard B/W paper developer. The citric acid is mixed from powder (the kind you buy at a health food store) at a concentration of about 30mG per liter of water, and the peroxide needs to be at least 12% concentration. We buy our peroxide at beauty supply shops in the form of a liquid known as 40V hair bleach. You want to get the liquid version NOT the creme version. There's also higher concentrations available (up to 35%) at health food stores for use in peroxide therapy. Standard drugstore peroxide is only 3% or less, not strong enough for this process.

The basic process is as follows:

1) Expose your paper in-camera at an exposure index (ISO) of around 3. You'll have to experiment with this to get an optimal exposure, depending on the color of the light and subject matter, and how much UV is in the light. B/W paper is sensitive to only UV and blue, with a bit of green sensitivity if it's multi-contrast paper. This process works on both multi-contrast and fixed-grade contrast paper.

2) Process the paper under safelights (or in a developing tank) in standard paper developer like Dektol. We use a dilution of around 1:3. Process for 3 minutes with constant agitation. The image should look like a slightly over-exposed paper negative.

3) Process in citric acid for 4:00 with continuous agitation. Mix the solution at a dilution of 30mG per liter of water. If you intend on doing multiple print runs through the same chemistry, it's advised to use a water rinse bath before the citric acid to wash off the residual paper developer (call this "step 2.5"). Near the end of the citric acid bath you can turn off the safe lights (or remove from the developing tank) and view the print under normal lighting, it should still look like a slightly over-exposed (i.e. dark) paper negative. If you're doing this outdoors, you may notice the negative image quickly turns pink with exposure to the UV of sunlight. This color should disappear later in the process.

4) Process the print in 12% H2O2 with continuous agitation for at least 3 minutes. Don't rinse the print after the citric acid, but immediately put it in the peroxide bath and start agitation. The print should begin to turn light toned with a fine layer of gas bubbles (foam) forming on the surface of the paper. Keep constant agitation until as much of the image as possible is bleached out. The ideal bleached print should look like plain white paper.

5) Process the print in a bath of sodium sulfite, mixed from powder at a concentration of 30mG per liter of water. Continuously agitate for 3:00. This bath will help prevent brown staining on the print. If you're processing outdoors under sunlight, you may notice the print suddenly exhibit a slight warmtoned positive image. This happens with some papers under the UV of sunlight.

6) Process the print in water with continuous agitation to remove any residual sodium sulfite before the next step.

7) Transfer the print back to the first paper developer bath (Dektol). It should immediately form a silvery positive image. Process for 2:00 with intermittent agitation.

8) Thoroughly rinse the print to archival standards for best results.

Here's a quick clip of a 20" x 24" portrait undergoing the 2nd developer step, after the negative image has been bleached away. Notice how quickly the positive image forms. (Clicking the image will link to the video on Flickr.)

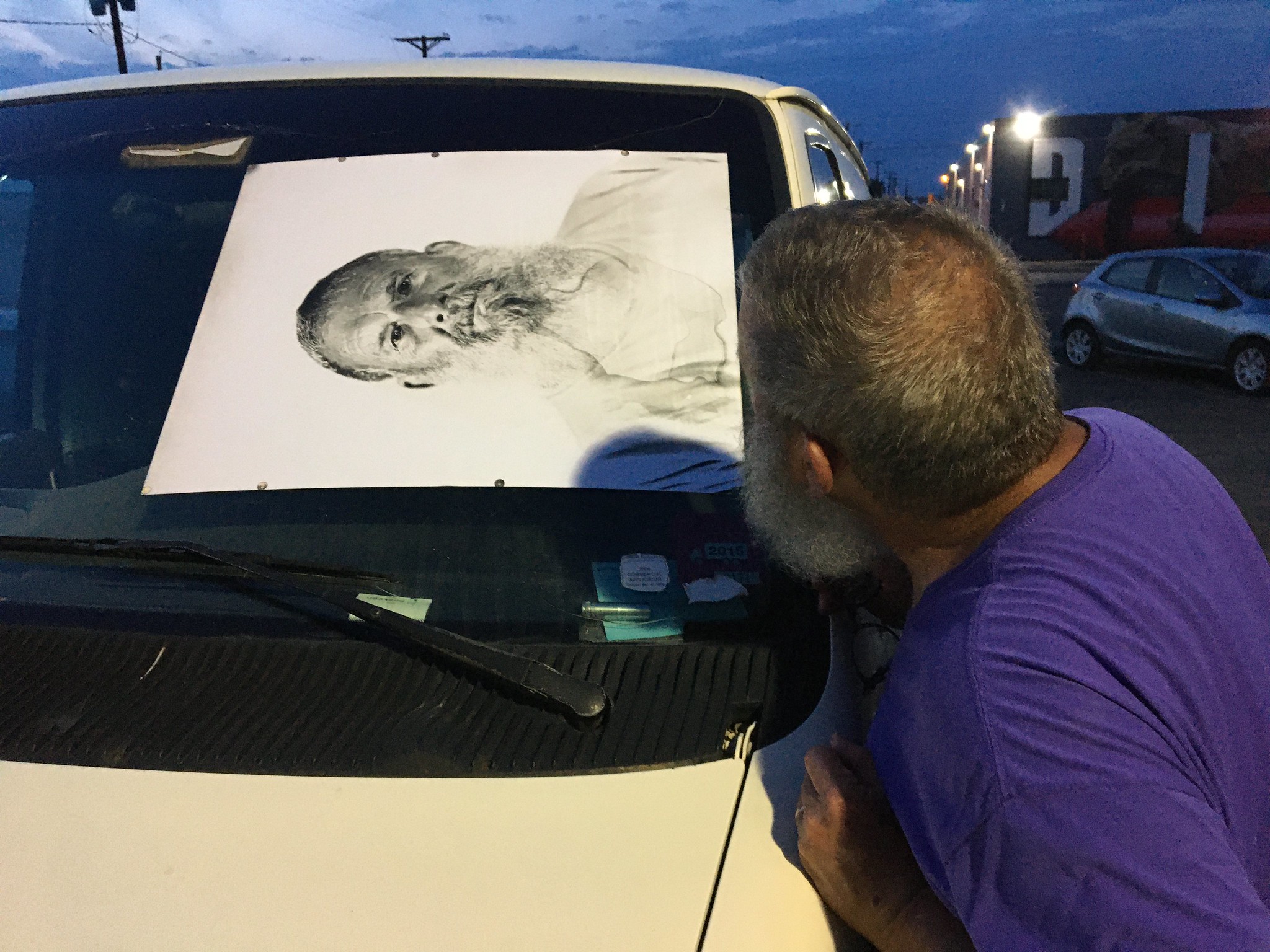

We did a series of test portrait demonstrations at QueLab, Albuquerque's maker space, with some of the members participating as willing test subjects. Here are a few images from that session:

The processed print still in the self-developing back.

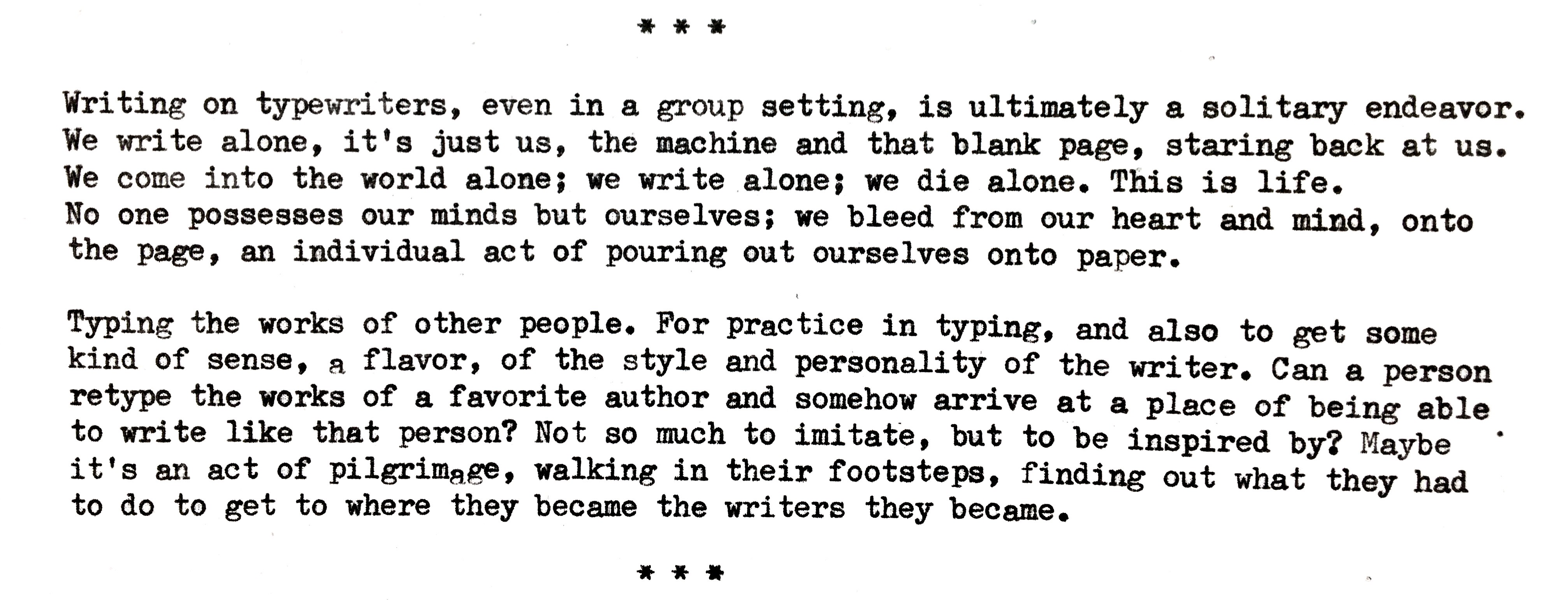

We found a car windshield to be convenient for drying wet prints outdoors.

Ethan used two high-power strobes with reflectors to get these indoor exposures, with a white projector screen as a backdrop. Note the processing artifact center bottom, caused by inadequate chemistry volume and/or agitation.

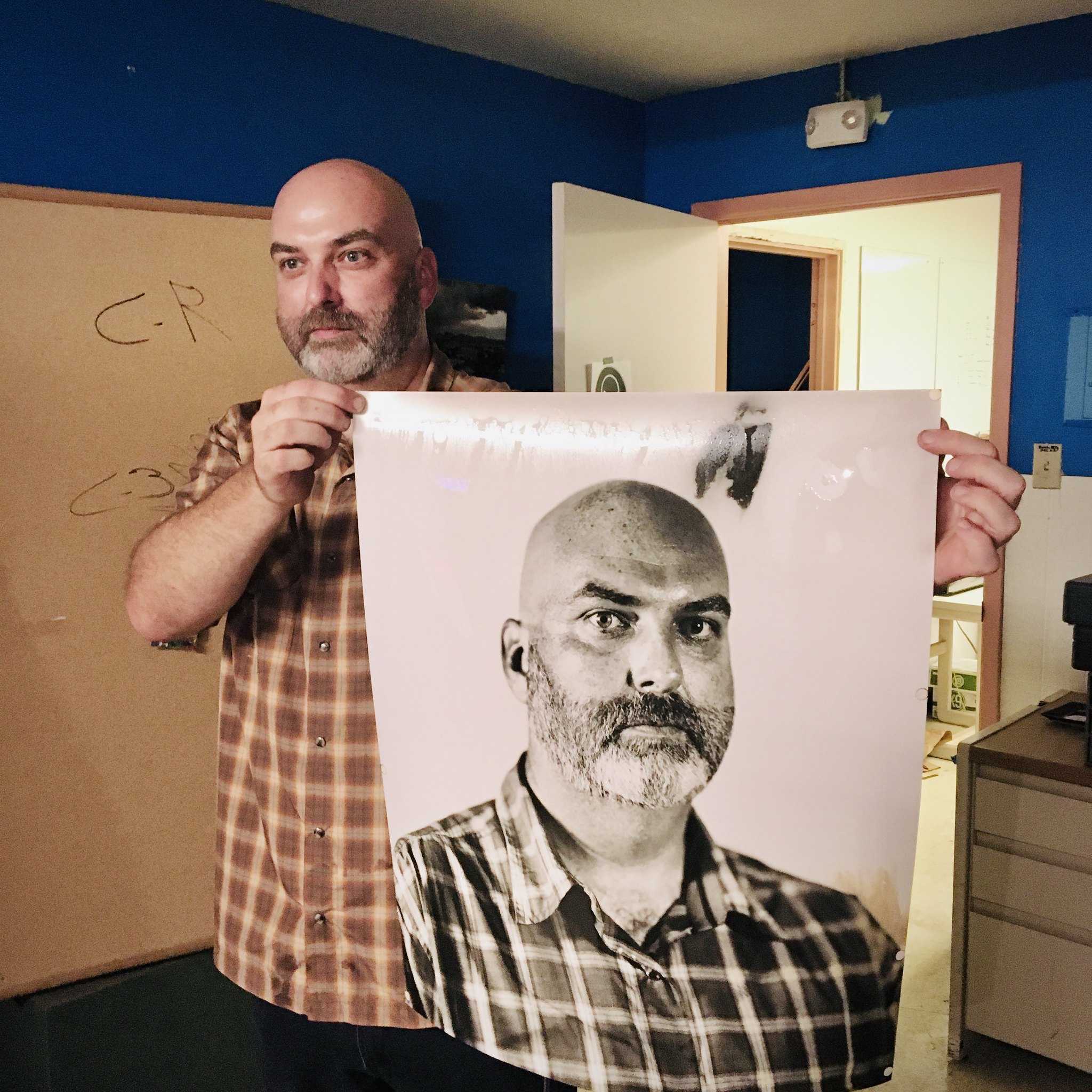

This was our first test subject of the day. Note the several processing artifacts, above his head and again center bottom. This mega-sized self-developing back demands proper chemistry volumes and agitation, a challenge given the weight of the back.

This was the best print of the day, despite the processing artifact above the subject's head.

Note also the brown stain lower right. Fresh sodium sulfite is supposed to take care of this.

Note also the brown stain lower right. Fresh sodium sulfite is supposed to take care of this.People have asked me for a layman's explanation of how the reversal process works. My explanation starts with the first development step, that makes a negative image. The darker parts of this image are metallic (developed out) silver, representing the bright parts of the scene, while the lighter parts of the image, representing the darker parts of the scene, are unexposed silver halides still in the emulsion, and look white because you're seeing the paper media behind the emulsion. Then the combination citric acid + H2O2 steps bleach out the metallic silver image, leaving the white print paper with undeveloped silver halides intact in the emulsion, that exhibit a density profile proportional to the inverse of the negative image; i.e. the parts of the paper that used to have a dense (negative) highlight are now very thin in residual silver halides, while the shadow portion of the negative image (the lighter parts) still have plenty of silver halides left. Then the emulsion is generously exposed to light (this happens after the citric acid step and on through to the end of the process). When exposed to the developer a second time, the residual silver halides now develop out to form a positive silver image, as the parts of the emulsion weak in halides remain very light, representing the positive image highlights, while the parts of the emulsion rich in halides develop out very dense, representing the image shadows.

I've been asked if the completed positive print needs to be processed in a fixer solution. It shouldn't need fixer because there shouldn't be any unexposed silver halides left in the emulsion to fade over time. But a thorough archival wash is a good idea.

I hope to continue my own exploration of this process, in the hopes of making it more reliable and less error-prone. We've already made some changes from the original process as I discovered it on APUG several years ago. Initially the citric acid and peroxide were mixed in one solution. Then we started doing them as separate steps, and we'd go back and forth between them in several stages until the print was adequately bleached. More recently, Ethan has had good success with a lengthy citric acid step first, to saturate the emulsion as much as possible, followed by one lengthy peroxide bath to complete the bleaching.

Given the relative cost of the various chemicals, the citric acid and sodium sulfite should be used as one-shot chemicals and disposed of after one use. They are very inexpensive when mixed from a powder form.

Paper developer has been a problem, especially the liquid concentrates, which can age and oxidize once the container is opened, resulting in faint, washed out tones lacking dense shadows. We've recently had good results using Dektol mixed as a one-shot developer from powder. This is against Kodak's own recommendations, as they stipulate to mix the entire package's powdery contents to make a gallon of "stock solution," then dilute this stock solution for your working solution. The problem is that the stock solution has a limited lifespan once mixed with water, just like liquid concentrate once opened. Critics of using small amounts of powdered Dektol say that the various constituent chemicals in powder form are not uniformly mixed in the package, hence the results could be inconsistent. Ethan and I contend that the contents of the package should be transfered to a large double-ziplok freezer bag and generously agitated to thoroughly mix the contents together. Then keep this bag sealed until such time that you need to take a small spoonfull to mix up a batch of developer. This seems a much more reliable method of ensuring fresh developer is always available.

An alternative would be to have the constituent chemicals on-hand to mix from powder, directly before use, via such sources as Photographer's Formulary.

The other process issue is the lifespan of the peroxide. The solution, as it gets reused, ends up being saturated with metallic silver, much like used fixer. We haven't looked in detail about filtering out the silver, or "auto-plating" the silver onto steel wool, as is often done with used fixer. It also gets contaminated with carry-over citric acid, which builds up in concentration through repeated use. So for now we use it until it starts to look cloudy, then we use a fresh bottle. The silver-saturated peroxide should be disposed of as you would used fixer.

There are some safety concerns to consider with this process, as there would be with any kind of chemical processing. Paper developer can be a mild irritant, and years of direct contact to developers containing metol can result in rashes and other allergic reactions. A strong citric acid solution can be an irritant, so keep your hands out of it. Mixing any kind of chemical in powder form can result in airborne particles that can be an inhalation hazard, so the precaution of a simple respirator mask can do a lot to mitigate that risk. Concentrated hydrogen peroxide should be kept off the skin and away from your eyes. Use safety glasses and don't get it on your skin. You'll notice an immediate white discoloration to your skin upon contact, and perhaps a burning sensation. Immediately wash with fresh water if this happens. Use gloves and eye protection. Also be aware that strong hydrogen peroxide is an oxidizer. Keep it away from strong solvents, corrosives and other flammables, and heat sources.

Using the huge 20" x 24" self-developing back can be a challenge, due to its weight and size. Use of a large waste tray to process over is strongly advised, to avoid drips and splashes that can end up on the floor, or your shoes (or exposed feet or legs). There's a definite learning curve to making this process neat and safe, but the results can be outstanding.

I'd like to thank Ethan for giving me access to his workshop and the inner workings of his design and build process. It's been a fascinating journey.

Labels: ABQwerty Type Writer Society, Ethan Moses