Thoughts on Mapping the Writer's Tool-Space

You can usually tell when I’ve hand-written these pieces, prior to typing (at least, I can tell); they have a different rhythm, flow and feel. It has something to do with the interaction between a writer and the writer’s tools.

Each tool or method of writing has with it a unique blend of attributes, advantages and disadvantages, which have the effect of forcing the writer, either through convenience or the hard limitations of systemic principles, into a narrow window of behavior. Handwriting is slow, letter-by-letter, in linear (serial) order; while the word processor is almost entirely random-access, but limits one’s field of view to a few paragraphs at a glance.

Given the variety of writing methods at our avail, due no doubt to the recent explosion of information technology, in conjunction with a near proximity to recently outdated methods whose physical artifacts still remain functional (i.e. typewriters, old fountain pens, etc.), we exist at a unique time in technological history when such diverse tools and methods can be evaluated and compared in actual use, rather than being relegated to dusty museums or history books. What we require therefore is some straightforward method of evaluating writing tools by their effect on our usage patterns; we need a good, old-fashioned writer’s tool smack-down.

More precisely however, we need to agree upon some parameters, a common language of terminology on which to base our evaluations. One method is to map the Writer’s Tool-Space: to define several axes of freedom, then quantify each tool or method as to where it falls out within that space.

One obvious, perhaps the most obvious, parameter is convenience of editing; not just the initial layout of characters, words and phrases but how easily they can be rearranged, manipulated and revised. We could call this flexibility of editing “compositional freedom.” The full spectrum of compositional freedom ranges from entirely random, whereby letters, words, lines, paragraphs and/or whole pages (even entire documents) are copy, pasted, cut or rearranged at will; to the restricted limitations of linear access only, whereby the document in question is a linear sequence of characters whose order is entirely and immutably fixed – etched in stone (literally or figuratively). Within these two extremes can be plotted the respective compositional attributes of virtually every writing technology or method imaginable, from literal characters carved into stone to symbols manipulated on computer displays.

Another systemic parameter useful to consider is how much of the document can be seen, or visually accessed, at any one moment, during the actual writing process. This characteristic is hard-wired into the structure of the physical media being employed, and can range from entire pages viewed at one glance (in the case of handwritten sheets or storyboard layouts) to fractions of sentences (in the case of cell phone-based texting, and typewriting). Within these extremes, the entirety of the known methods of writing can be located in proportion to their ease of visual access.

Given these two major criteria for evaluating the Writer’s Tool-Space – visual access and compositional freedom - it becomes useful to compare the one against the other; implying some form of two-dimensional mapping, as illustrated herein. It seems probable that virtually any writing process, or collection of writing tools, can be found mapped within this Tool-Space, further implying that various means and methods can be evaluated, one against the other, by their relative locations within this space. For example, we might compare handwriting on paper against word processing, where we find that handwriting permits a wider visual grasp of the document, albeit with minimal editorial flexibility; while word processing offers greater flexibility for revision, with a more restricted view.

We might also consider that the writing process itself often occurs in phases, each one requiring that certain attributes be enhanced, while others remain suppressed. For example, during the initial write there is often the need to purposefully minimize the ability to revise and edit, and instead to enhance the undistracted collecting of words, phrases and paragraphs. In this case many writers may find the more restrictive and linear access methods to be most useful. Conversely, during the later revision and editing phases of the writing process the need transitions to flexibility of editing, when methods such as the word processor become more expedient. Between these extreme stages of the writing process are intermediary phases when having a large visual scope of the document is important, while still retaining some ability to perform restricted changes and edits; it is during these intermediary phases that methods such as red line editing of typed, printed or written text is useful.

(Vector Diagram of an Example Writing Process, Mapped Onto the Writer's Tool-Space)

(Vector Diagram of an Example Writing Process, Mapped Onto the Writer's Tool-Space)It becomes axiomatic that the writing process itself (although varying from one person to another) could in general principle be mapped as a progression from the more compositionally restrictive to the more flexible, with the visual component representing a progression from the narrower to the wider view. Such a progression can be mapped as a vector within the Writer’s Tool-Space diagram.

It should also be recognized that individual writers would each find their own custom writing process, which will often vary considerably from one person to the next, such that these various processes can be mapped on the Tool-Space diagram as a series of vectors unique to each writer.

(Vector Diagram of a Variety of Writing Processes, Mapped Onto the Writer's Tool-Space)

(Vector Diagram of a Variety of Writing Processes, Mapped Onto the Writer's Tool-Space)For example, person “A” might initially compose his work using paper and pen; then red line edit; then perform the final stages of editing using a word processor. Person “B”, conversely, could be found to practice a regimen of composing on an Alphasmart device, and then perform final edits in a word processor. Person “C”, alternatively, could use the word processor for the entire writing process.

It is also possible that the same writer may use a multitude of different writing processes, depending on the nature and purpose of the writing. For example, a professional writer, employed by a media agency, would most likely use a word processor-based method for the bulk of their professional writing, yet revert to a more hands-on, linear approach for their personal writing.

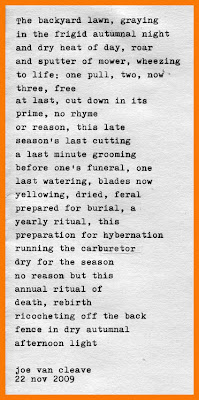

(My Initial Scribblings)

(My Initial Scribblings)I have only touched the surface of what is possible to understand about the process of writing by the evaluation of the Writer’s Tool-Space. There are also other dimensions of understanding worth exploring: for instance the speed of data entry within the writing process; or the dimension of the story’s granularity, from the finest detail of individual letters within words to the coarseness of the story’s overall arc of plot as viewed from the outline or storyboard level; or the aesthetic appeal of various writing tools and methods. Given the almost limitless possibilities to understanding the writing process, it seems that a mere two-dimensional diagram is entirely insufficient to fully illustrate the extent of the Writer’s Tool-Space. While it is of utmost importance for a writer, rather than fixate upon the tools and processes employed, to actually write, I believe it is of some practical value to consider the entirety of the Writer’s Tool-Space as a vehicle for the further improvement of one’s writing.

Given the near-proximity to the conclusion of 2009’s National Novel Writing Month project, it is anticipated that there would be some relevant feedback to this subject, based on individuals’ NaNoWriMo experiences. So, how about you; where do your writing tools, methods and process fall out on the Writer’s Tool-Space diagram?