Further Thoughts on Lumen Photography

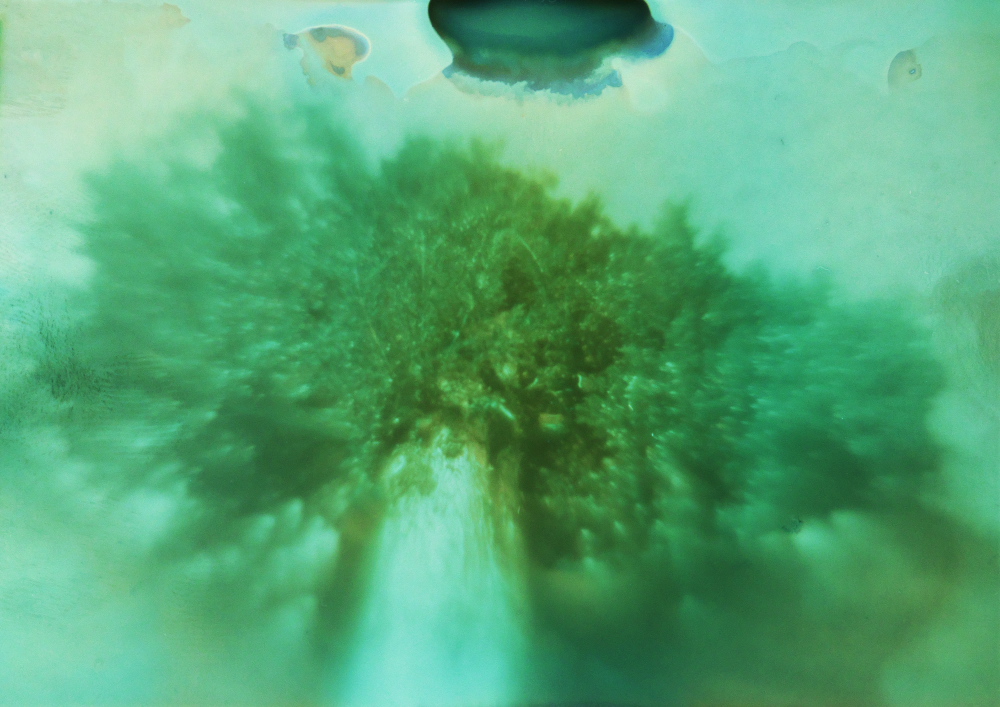

Pre-wetted with water, lens wide open, 3 hours 45 minutes exposure.

I've been consciously trying to make a lumen print every free moment I can. These aren't as quick as snapping a shot on a phone, or even hitting "print" on the computer. It takes many minutes, usually several hours in fact, for the image to form itself within the little paper camera upon the slip of photo paper inserted within. Even then, the image isn't ready to be shared. It has to be digitized, then post-processed into a positive.

When a camera can make an exposure in a minute fraction of a second, quicker than you can blink, you can't help but question the value of your participation in the process. Sure, you pointed the camera and chose the moment to press the button, but that's about it; all the magic happened in milliseconds of time.

But when the image takes literally hours to form, and even then is still in "raw" form, requiring further interaction, you can't help but think that here's a process you can get your head around. It's participatory, from deciding where and how best to set up the camera so it won't be moved or disturbed for several hours, to preparing the photo paper and loading the camera, to carefully setting the little box so it's pointing in the general direction you intended. And then the waiting, setting a timer and periodically checking on the camera to make sure it hasn't fallen over, worrying over it like a momma cat over her kittens, hoping the composition is right, hoping the light will be right, anticipating the results yet knowing, down deep, they won't be as good as you'd hoped.

All of this fussing, the extended exposure time required, fools you into thinking you're more involved in the outcome than you really are. It's still a matter of pointing the thing in the right direction, then opening the shutter to let light inside. The magic happens, not as a result of your cleverness, but despite our best intentions. It's the physical process, photons upon molecules. The trick to art, it reminds us, is in convincing others we're somehow responsible for the outcome.

For many years I was an avid pinhole photographer. I was attracted to the primal simplicity of the idea that light can form an image by mere projection through a small aperture. Yet, for the image to be fixed, some complicated process has to unfold, whether it be the chemical processing of silver gelatin film or paper, or a digital sensor. The only difference being the type of lens employed.

Once I'd discovered for myself lumen photography, another kind of primal process became apparent. The magic for me is more apparent than with pinhole, where the distinction is merely in the kind of lens employed. Here, the lumen image is due to the direct action of photons upon a silver gelatin emulsion. It's self-forming, it's light itself doing the etching, no further human interaction required except in the post-production phase, where the necessity of making the image a positive is more due to the inability of humans to directly appreciate negative images.

Lumen prints are developer-less, not like Polaroid prints, where the developing process seems invisible but is merely built into the print itself, a chemical pod squeezed between rollers as the print is ejected. The lumen process seems more like an act of nature. You boil down cattle bones, mix in some silver salts, spread a thin coating on paper, stuff it in a box and focus light upon it and, as if all by itself, an image is formed. Of course, in actual practice we usually let others do the boiling of bones and coating of paper, like Ilford or other manufacturers of photographic papers. Still, there's an element of mystery involved, as if to remind us that magic is built into the very fabric of the elements, but which we commonly dismiss under the rubric of "chemistry".

Silver nitrate or potassium nitrate? One makes images, the other blows things up. We get to choose. I am reminded of Alfred Nobel, the namesake of the annual peace prize awards, who was also the inventor of dynamite. In my mind there's this double-exposure formed, one layer being lions lying with lambs, the other layer crater-pocked fields in France, the smell of cordite, the broken minds and bodies of young men.

Photography, as it has advanced in technical sophistication over the centuries, begins to resemble as much the nature of potassium nitrate as it does silver nitrate. We aim guns; we aim cameras. We take a shot; we take a shot. We capture prisoners; we capture images. It takes a conscious effort of the will not to use the language of warfare when discussing photographic creativity, that's how ingrained these terms have become in the common lexicon of culture. It's all too easy to say "I've taken a picture," when you really mean you created a picture. Taking sounds like appropriation, winner take all, the business of empire-building, losers left in the wake. Creativity, I'd like to think, should be a collaborative process, a making of something beautiful, where once there wasn't an image, now there is, ex nihilo, as it were, being made in the creator's image; or, at least, symbolic of such.

Lumen prints appeal to me also because they remind me of the very formative years of photography, obscure and difficult processes requiring lengthy exposures and still subjects. You couldn't make a lumen print of a quick-action sporting event, for example, unless the intensity of your light source was on the order of a nuclear detonation. I'm reminded of a supposedly true story told in John McPhee's book The Curve of Binding Energy, where a nuclear physicist (Ted Taylor, if memory serves me), observing a nuclear test, set up a cigarette in front of a small parabolic reflector and, shortly after the pikadon - Japanese for "flash boom," he reached down and took a drag off the smoldering ash. You could do that today with a magnifying glass aimed at the sun, but it would still take many minutes or hours in the same setting to capture a lumen print image of the scene.

Darkroom photographers have known for a long time that a clipping of silver paper, left out on a table will, over time, slowly turn a subtle hue of pink or purple. But to employ that phenomenon into a usable photographic process requires fast optics, to record the image with a semblance of convenience. If one chooses a large format camera and lens, the main limitation is the maximum aperture available on standard large format lenses. The fastest optic I have available in a conventional large format lens is a 127mm Kodak Ektar lens from the WWII era. F/4.7 doesn't sound all that fast by today's bokeh-obsessed standards, but it's barely adequate for the process. Since sub-second exposure times aren't necessary for this process, having a lens with an integral shutter isn't necessary. Still, finding a lens with adequate image quality that projects a large enough image circle is no small task. I also have a Fujinon Xerox machine lens, of f/4.5 aperture, but it requires a paper size of at least 8" by 10" for a normal angle of view. Smaller lenses, like magnifying glasses, will cover the 4" by 5" format better, but being of a single-element meniscus design, exhibit severe off-axis aberrations.

I've found such improvised optics seem to work well with the lumen process only because the resulting images, with their blurry edges, have a dream-like quality in keeping with the ephemeral nature of lumen photography. A sub-f/4 lens from a medium format camera, if one could be found, would be ideal for creating sharper images, if that were one's goal.

I first became aware of lumen photography from artists who were employing pinhole cameras to make exposures of the sun's path across the sky using exposures lasting many weeks or months. It was only because of the work of photographer Jorge Otero, from whom I acquired a Lumenbox kit camera, that the possibility of scenic landscape lumen photography became evident. Otero, who goes by the social media moniker of Joterman, began using fast, single-element lenses with photo papers, while also pioneering the technique of pre-wetting the paper with water in an attempt to speed up the image capture effect.

It's exciting to be at the pioneering phase in this process, reminding me of what it might have like in the early 18th century when photography was first being developed. Much has yet to be discovered about how to speed up the image-formation process. I've thought about running a series of experiments involving dousing pieces of photographic paper in various household liquids to see what results. Coffee, ketchup, hot sauce, soy sauce or bleach - what might they reveal? Probably a huge mess. A liquid-proof camera seems necessary, at the very least.

Lumen print photography, involving fast lenses to create pictorial images, is a process that could only have been practical within the last few decades. Given the resulting negative's ephemeral nature - the prints remain light sensitive and hence are continually at risk of fading from subsequent exposure to light - they require digitization through quickly scanning or photographing with a digital camera, after which the resulting image file can then be post-processed, by inverting the tones in photo editing software, to create a file that can be digitally printed. It's an intrinsically hybrid process, which represents a fundamental irony, given the primal nature of the processes involved.

Taking a first brief glimpse at an exposed lumen print under subdued lighting is always accompanied by the expectation of a fresh discovery. No two prints are the same, while the color palette of the negative itself is often more pleasing than the hues resulting in the reversed positive digital image. I'd like to try inverting the monochrome portion of the image to create a positive rendition, and superimpose that with the tones present in the original negative, using the layers tool in a program like Photoshop, to create a hybrid positive/negative version. Or perhaps some semi-reversal chemical process, like solarization, might be found practical.

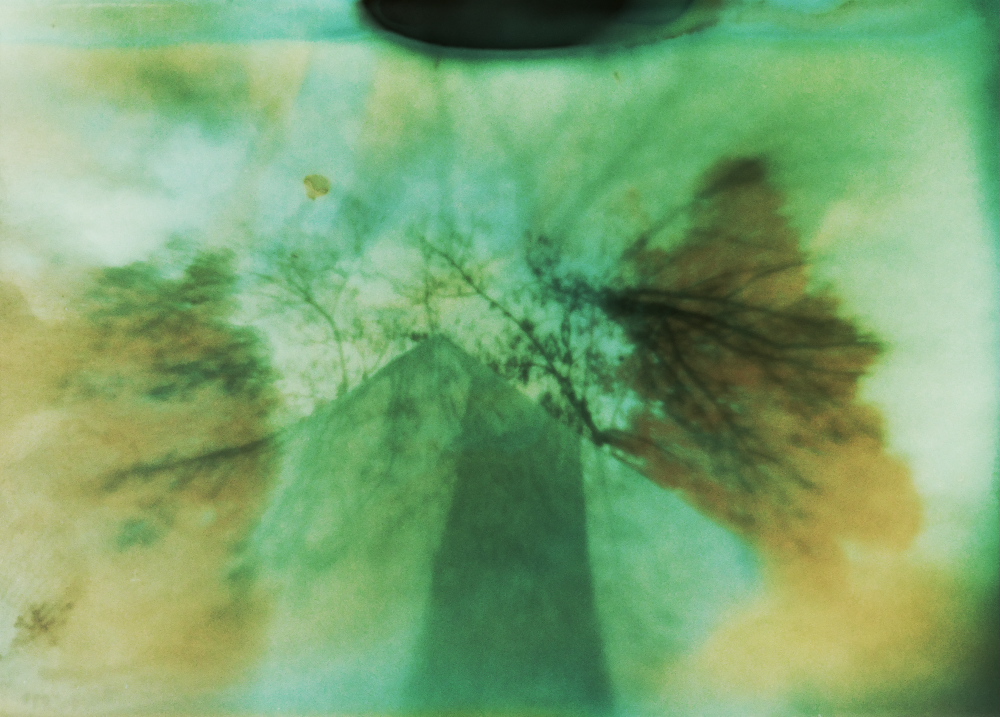

I've also found the resulting image can vary widely, depending on the intensity of the scene's illumination, the color of the subjects, and the exposure times involved. Pre-wetting with water also changes the color palette somewhat, while in my camera also results in the pooling of water near the bottom edge (the image's top), resulting in globs of dark tones that adds to the mysterious outcome.

I have a cobbled-together 8" by 10" format sliding box camera (employing one box nested inside another for focus), that's currently fitted with a single element meniscus lens. Perhaps I should rig up that fast Fujinon Xerox lens and see what transpires.

I'll be sure to share my results herein, and on my YouTube channel.

Some recent lumen print images:

Pre-wetted with water, lens wide open, 2 hours 15 minute exposure.

Pre-wetted with water, lens wide open, 1 hour double-exposure.

Pre-wetted with water, lens wide open, 1 hour exposure.

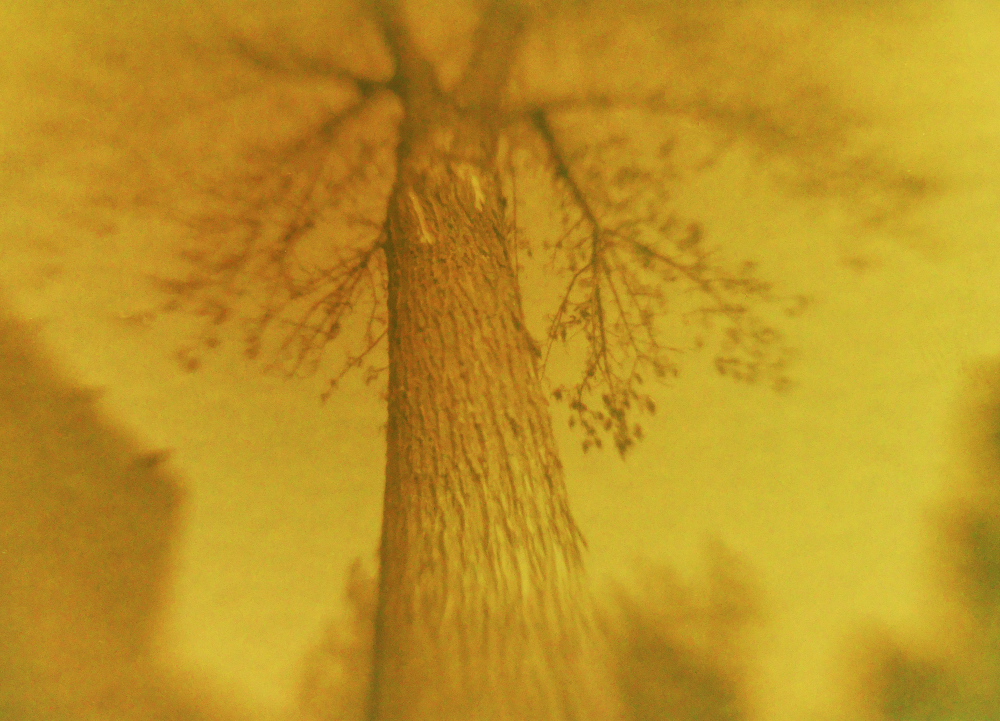

Exposed dry, lens stopped down, 3 hours 9 minute exposure.

Labels: Lumen prints, Lumenbox