Tinkering With Old Cameras

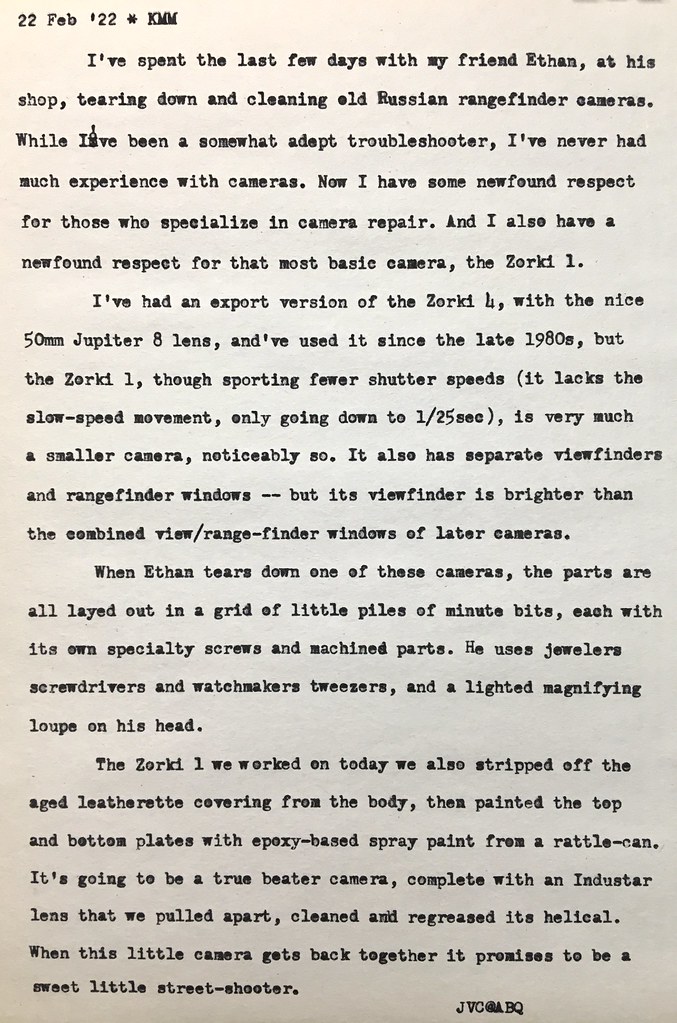

Joe cleaning Zorki 1 parts

I was once a VCR and camcorder technician, back in the 1980s, when I was younger, had better eyesight and steadier hands. Even so, it was challenging, especially camcorders with their innards crammed with compact circuit boards connected together with fragile ribbon cables, and their miniature transport mechanisms that were a marvel of precision miniaturization. Electronic problems were approached using structured problem solving -- troubleshooting -- involving voltage and waveform measurements, assisted, if you were lucky, with service literature from the manufacturer.

But before these marvels of electronic and mechanical miniaturization there were all-mechanical cameras. Oscar Barnack, working for Leitz optics, around the WW1 timeframe invented the first practical rollfilm camera using 35mm motion picture film, which eventually became what we know as the Leica rangefinder. A dense, compact metal chassis crammed with precision machined parts and featuring rangefinder focusing mechanically coupled to jewel-like miniature lenses, Leica rangefinder cameras have remained even today the pinnacle of mechanical camera engineering. But back in the 1930s Soviet manufacturers began copying the early Leica screw-mount (so called "Barnack") rangefinder cameras, with sometimes dubious engineering and build-quality.

I've been using one of these, the Zorki 4, made in 1971, with its diminutive but elegant Jupiter 8 lens, since the 1980s. The camera has been remarkably reliable, considering I used to leave it in the glove box of my car, winter and summer; I've often wondered if its internals weren't lubricated with whale oil, because it never seems to have been bothered by the cold, despite its all-mechanical operation.

A few weeks ago my friend Ethan Moses began educating himself on Russian rangefinder cameras, by buying a handful of these old cameras from online auction sites. In the intervening time since they've arrived on his doorstep, he's learned to tear them down, service them and put them back together, mostly in better shape than when he started, with the exception of one or two early on that served as training aids. These all are, in some form or another, direct descendants (or knock-off clones) of Oscar Barnack's Leica, albeit with mostly inferior mechanicals. The Fed models (named after Felix E. Dzerzhinsky, head of the Soviet secret police) were the worst of the lot in terms of design and build quality, while the Zorki models were noticeably better. My camera, the Zorki 4, was probably the height of Soviet rangefinder camera technology, in terms of build-quality and features, but it is the little Zorki 1 that surprised both Ethan and I.

The Zorki 1 lacks the slow-speed timer mechanism of the later Zorki 4, meaning the slowest timed shutter speed is 1/25 sec. It also has separate rangefinder and viewfinder windows, meaning you first focus on your subject in the rangefinder window (by turning the lens focus ring and aligning the double images where you want the image to be most sharply focused), then move your eye to the viewfinder to frame your shot. The Zorki 1 also lacks the nifty adjustable eyepiece diopter of the Zorki 4, a boon to eyeglass wearers. But where the Zorki 1 lacks in features it makes up for in diminutive form factor. Compared next to each other, the Zorki 1 top plate barely pokes above the upper trim line of the much taller Zorki 4.

Ethan and Zorki 1 in hand

Ethan and Zorki 1 in handThough metallically and mechanically dense in heft, the Zorki 1 fits in the hand very comfortably and is easy to carry around, especially with a collapsible screw-mount lens attached. It also lacks strap lugs, meaning you either have to use the original leather case (which are rather rare), or attach a 1/4-20 strap lug fitting to the tripod socket. I think it feels best in hand sans strap altogether. Also lacking a built-in light meter, the best way to use these cameras is use a light meter app on your phone, take a reading, transfer the settings to the camera and then just go shooting and not worry about further metering unless the light significantly changes, relying instead on the exposure tolerance of film. The ultimate in simplicity.

I often hang out at Ethan's on Tuesdays, and these last few weeks I've watch him tear these cameras apart, describing to me each part's function, watching him learn the ropes as he becomes more adept at servicing them. Sometime after Ethan gained confidence in servicing Russian rangefinders he tried his hand at a Japanese-made Canon rangefinder.

In comparison to the more primitive Soviet cameras, the Canon seemed over-engineered in complexity, making it much more difficult to service. What makes this ironic is these Canon rangefinder cameras don't seem to garner the prices on the used market of the original German screw-mount Leicas, meaning there's little sense in buying one if it needs servicing, you're better off just getting a Leica instead.

Yet, despite the challenges, working on the Canon was a valuable education for both Ethan and I. Based on his past experience with the Soviet cameras, Ethan could identify each module of the Canon's mechanism, noting the similarities and differences in how specific functions were carried out. The analogy that came to my mind as I observed Ethan tear down and rebuild these intricate mechanisms over the course of the last few weeks is that they serve as a form of mechanical logic: one linkage pawl gets held back by the slow-speed timer, preventing the second shutter curtain from releasing until the slow-speed clockwork winds down, then the second shutter curtain is released, ending the exposure. In a digital camera this logic would instead be performed by firmware in a silicon chip, but in these cameras the "programming" was strictly by means of an intricate interaction of mechanical parts.

Labels: Soviet cameras Zorki cameras Zorki 1 Zorki 4 Ethan Moses Camera repair